from: http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,2144,2071791,00.html

A Stroke of Genius? A New Recipe for Coal

Markus Antonietti from the Max-Planck Institute has developed a simple

but ingenious way of producing coal using biomass - such as waste from

the garden or leaves from the local forest.

The process is environmentally friendly, as the only by-product

is water - not carbon dioxide which would contribute to global warming.

Antonietti has successfully managed to develop this method so that it

could be used for commercial coal production. Such coal could just be

used for heating purposes, but it could be used far more effectively in

electricity and gasoline production. The 70 million tonnes of biomass

that Germany produces every year would be sufficient to cover the

country's energy needs.

We take a closer look at this potentially revolutionary discovery.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

What is this chemist doing for in the woods armed with a pair of scissors?

He's gathering the ingredients for a very special recipe.

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

Markus Antonietti from Max Planck Institute for Colloid and

Interface Research: "I'm collecting leaves and twigs. We want this

material to solve one of the great problems of the age."

It's the problem of the planet's energy supplies. Markus Antonietti

wants to use a technique he's developed to cook up some coal, based on

the way nature does it.

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

But instead of millions of years, his method takes only a few hours.

But stop! First the ingredients.

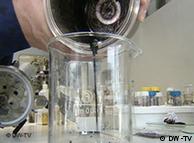

The biomass goes into the autoclave, a kind of pressure cooker.

Leaves, pine cones and other plant residues are put into the pot. Water

goes in, too, along with a citric acid catalyst. The mixture releases a

lot of heat - in other words, energy.

Markus Antonietti from Max Planck Institute of Colloids and

Interfaces: "We underestimated this when we started. We could calculate

how much energy was stored in the sugar - in the leaf material. But the

first time - as you see - we had a runaway reaction, which is obviously

dangerous, so we need to carry it out under safe conditions."

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

Now the reaction is being carried out in an experimental "kitchen"

on the roof of the institute. Here it's no problem if the hydrothermal

carbonization, as the process is called, causes minor explosions.

It's all part of the joy of experimentation for the 46 year old

director of the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces.

Antonietti says he's only been able to pursue this simple idea since

establishing himself in his field.

It really is a simple reaction. The ingredients just have to be heated....

...for 12 hours at 180 degrees Celsius.

And the coal is ready.

The single major by-product of the reaction is water, which can

filtered off. In contrast to other biomass techniques this reaction

does not generate carbon dioxide. And it gives a higher-energy product,

which even smells acceptable.

Markus Antonietti from Max Planck Institute of Colloids and

Interfaces: "It has a strong smell. (Very masculine.) Like tobacco."

If it were up to Antonietti, this reaction could go large-scale. The

50,000 tonnes of plant refuse that accumulate yearly in Berlin could be

converted into 20,000 tonnes of usable carbon.

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

Markus Antonietti from Max Planck Institute of Colloids and

Interfaces: "The Max Planck Society only does basic research. But with

enough engineering back-up, we could establish this in two to five

years. It's very simple, there just has to be support for it."

Could this laboratory coal be produced on a large scale? Antonietti

says it makes economic sense. The energy needed for the heating is no

greater that that required by other methods.

Until that day comes, the Max Planck scientists intend to go on with their research.

They want to study their laboratory coal in detail. This is the structure of a pine cone before ...

... and after carbonization. But not all coal is alike.

Markuis Antonietti from Max Planck Institute of Colloids and

Interfaces: "Like in a restaurant you can have your steak rare or well

done. We can adjust our coal to be just a bit refined, or we can cook

it until it's like hard coal. One end of the spectrum is topsoil, the

other is hard coal."

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

When the researchers cook their coal mixture for just five hours, the result is topsoil,

This nutrient-rich earth can be used to help barren landscapes bloom.

Soft lignite requires nearly as much cooking as hard coal. But in

order to get energy out of the laboratory coal, it doesn't necessarily

have to be burned.

Markus Antonietti from Max Planck Institute of Colloids and

Interfaces says: "We are dreaming of a carbon fuel cell. That would be

direct electrochemical conversion of the coal, without the actual

burning process. Other applications are in chemistry, for example,

directly making gasoline out of the coal."

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

Bildunterschrift: Großansicht des Bildes mit der Bildunterschrift:

The scientists intend to pursue those dreams, using nature as a

model. Their next project is to make petroleum - which is a stage in

the production of coal. So sometime in the near future these laboratory

visions may find a place in everyday life....