Messages from the dead: The drowned son who returns for bedside chats and other stories from "Opening Heaven's Door"

Thought death was clear but? A new book, Opening Heaven's Door, will challenge your views. In the second part of our serialisation, bereaved people recall visits by dead loved ones

A humid night in summer. Ellie Black wakes at around 3am and her eyes focus on a figure at the end of her bed. It's her father, from whom she's long been estranged. Now fully alert, she watches him as he tips his hat and bows with a flourish. Then he's gone.

The following morning she relates the experience to her daughter at the breakfast table. Later that day the phone rings - with news that her father died in the early hours. A tall story? Not at all.

Telepathy

Research in Wales, Japan, Australia and the U.S. shows that between 40 and 53 per cent of the bereaved receive some kind of signal or visitation when someone close to them dies.

Usually they sense a presence; sometimes they actually see or hear one. Psychiatrists have labelled these experiences 'grief hallucinations', though they have not yet been studied neurologically.

In 2012, the psychologist Erlendur Haraldsson published a comprehensive study he'd done on 340 cases of extraordinary encounters with the dying.

Usually people encountered their fathers or mothers - suggesting that the parental impulse to connect and reassure continues past death.

About a quarter of his subjects saw or heard the dead person at the hour of death or within the day it occurred. In 86 per cent of these cases, they weren't yet aware of the death by ordinary means.

Some surveys report that about half of all these telepathic experiences occur in dreams. A musician, Rory McGill, told me that on the night his father died, he had a vivid dream in which he climbed onto his father's bed and held him in his arms. 'But in an instant, I was standing alone in the room - he was gone, and the bed was empty and neatly made,' he recalled.

The next day, his mother phoned: his father had died unexpectedly while Rory was dreaming about him. A mere coincidence? Highly unlikely. A review of 'spontaneous telepathy' studies concludes that the odds against chance are 22 billion to one.

So, do we have a form of consciousness - a way of knowing - that has yet to be fully explained?

Intriguingly, studies of twins separated by distance seem to confirm that something odd is going on.

One of the first of these studies monitored the electrical impulses of the twins' brains. The scientists found that when one twin was asked to close his or her eyes, which causes the brain's alpha rhythms to increase, the distant twin's alpha rhythms also increased.

Many later twin studies had similar findings. In 2013, a study of British twins reported that 60 per cent felt they'd had telepathic exchanges. Among identical twins, 11 per cent said they had frequent exchanges with their sibling, including shared dreams.

Other studies of telepathy by University of Virginia psychiatrist Ian Stevenson explored how people could know that someone physically distant was dying or in distress. Stevenson started by analysing 165 meticulously researched historical cases. Nearly 90 per cent had occurred, he discovered, when the person was awake, rather than asleep or dozing.

Two-thirds involved news of an immediate family member. Eighty-two per cent involved death, a sudden illness or accident.

But people did not, apparently, pick up on one another's good tidings.

'Is it that the communication of joy has no survival value for us, while the communication of distress does?' Stevenson wondered.

He then moved on to 35 contemporary cases. And one startling conclusion from these was that a third involved violent death.

His findings were replicated in 2006, when Icelandic researchers found a dramatically higher number of abrupt or violent deaths in telepathic cases.

In addition, there were many accounts from both World Wars of a soldier's family or loved one suddenly waking in the still of the night. In that instant, they knew the soldier had died - and a telegram later arrived to confirm this. Perhaps, Stevenson mused, there was something in the emotional quality of the event - a thunderclap of fear or pain - that carried like a sound wave across water.

In more than half of the cases, the person who received the message was driven to take some kind of action - such as making a phone call, embarking on a frantic trip or changing holiday plans.

One woman drove 50 miles home in the middle of the night after suddenly gleaning that her teenage daughter was in trouble. It turned out their house had been broken into by armed intruders, with the daughter inside.

But how do you know that the news you've just received telepathically is correct? No one has yet fathomed this mystery. But Stevenson discovered 'a feeling of conviction' was one of the characteristics that separated telepathic communications from ordinary dreams and anxious imaginings.

There were two other factors that made people sit up wide-eyed and reach for the phone or take other action. One was if the person in the crisis specifically focused on the other person during the moment of danger. This seemed particularly true of parents responding to children.

The second factor was the possibility that the person receiving the distress call had experienced previous psychic communications - suggesting that some people just have a gift for this. Janey Acker Hurth, for example, not only sensed her daughter's (non-fatal) collision with a car, but also her father's sudden illness a few years earlier.

Back then, when she was newly married, she'd awoken to 'a feeling of deep sadness, an impression that something was wrong'. The feeling intensified and she began to sob.

Then, when she was making breakfast, she cried: 'It's my father! Something is terribly wrong with my father!' Her dad had gone into a coma during the night and died shortly afterwards.

Stevenson was struck by how this type of information sometimes gradually came into focus. People like Mrs Hurth, he concluded, 'may scan the environment for danger to her loved ones and, when this is detected, tune in and bring more details to the surface of consciousness'.

In the Eighties and Nineties, a British neuropsychiatrist, Dr Peter Fenwick, of King's College, London, appealed to the public for cases of what he called 'death-bed coincidences', and amassed more than 2,000 accounts.

Typically, one woman wrote to him about the suicide of her husband, from whom she'd recently separated. She'd awoken at 3am in 1989 from an intensely vivid dream in which her ex was sitting on the bed, assuring her that he'd found peace.

'I got up, did some work I needed to do and two clients phoned me around 8am,' she continued. 'I freaked them out completely as I told them I'd be taking some time out because my husband had just died.'

She didn't yet objectively know this to be true. But when she let herself into her former husband's flat, she discovered his body.

In her case, the person in distress hadn't sought help - instead, he'd apparently sent a message of reassurance after his death.

In other cases, people may be telepathically sharing the calm and peace they feel as they die.

Stevenson concluded: 'It's altogether probable that important, unrecognised exchanges of feelings through extrasensory processes are occurring all the time. Even if we can only observe it occasionally - and usually between persons united by love and during a special crisis - this should arouse our curiosity.'

Shared Pain

On the evening his father died of lung cancer, sailor Raymond Hunter felt as though his lungs were collapsing and he could scarcely breathe.

'I remember grabbing my mouth, forcing it open to help me breathe. I was fighting for all I was worth, but the pains were unbearable,' he recalled afterwards.

Unbearable pain - now, that's not something you shake off as a strange dream. Particularly when you later discover that your father died in that very moment.

This abrupt and violent experience of another person's dying symptoms has been noted by some researchers, though it remains almost completely unexplored.

Psychiatrist Ian Stevenson has suggested it could be a kind of telepathic extension of a phenomenon in which people who live together sympathetically take on one another's symptoms or moods. But that's only a theory.

A particularly vivid instance involves a woman in her late 30s.

'I was awoken around 2am by the sound of my heart breaking. I know that sounds really odd, but I heard it crack and felt my chest sort of splitting,' she recalled.

'The next morning I got into the car to drive to work. I was sitting at traffic lights when I felt this pressure on the side of my face. I distinctly remember that the pressure was that of a cheek lightly pressed against mine, sort of cuddling me.

'The feeling I was filled with at this time was one of love and support - it felt fine. I then felt a hand holding my hand and felt it had no middle finger. And then it dawned on me.

'It was my dad's hand; he'd lost his finger in a building site accident when I was a little girl.

'I returned home after an hour to be met by my husband's words: "Your dad's gone." Apparently, he'd died from a massive heart attack during the night. I wasn't at all surprised.'

Why should the dying want to share such agonies with the people they love? No one knows.

But one thing at least is clear: no one in their right mind could dismiss these visions as wishful thinking.

Return of the Dead

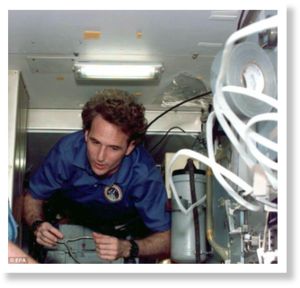

Two hundred miles above Earth, Jerry Linenger was working on the space station Mir when he suddenly became aware of the presence of his father.

It was 1997 - and his father had died seven years earlier. A conversation ensued in which the older man spoke of his pride that his son had realised his dream of travelling in space. Linenger was deeply moved.

Later, however, he chose to interpret his father's presence as nothing more than a projection of his imagination. And yet, at the time, he had derived great consolation from the encounter.

Nor was his experience by any means a strange aberration. In fact, it's estimated that around half of all bereaved people - in all cultures - at some point register the presence of their departed loved one.

According to a study done in 2006, 84 per cent of the bereaved were in good mental health at the time. And only 5 per cent found the encounter negative or distressing; for the majority, it was profoundly comforting.

Visual perception of the presence seems to be the rarest. In another study, only about 5 per cent actually saw the dead person; about 15 per cent heard him or her; and the rest had partial impressions, such as feeling hands on their head or noticing a distinct presence in the room.

Unlike our conception of ghosts, these presences can physically react with the material world.

The writer Nancy Coggeshall, for instance, felt the presence of her partner twice while lying in bed, five months after he died in 2002. 'I felt someone lying down beside me, and I felt the impact of [his] weight on the mattress. The second time, the pressure was so great, I rolled over and asked: "Who's there?" ' she told me.

Karen Simons, who works in advertising, recalled a similar experience in 1994, after her father, a farmer, died of a heart attack.

'After Dad's death, I began driving his big, old Ford Taurus,' she told me. 'It was comforting, in the way you hang on to people's shirts. But that's all it was. Until about six weeks after he died.

'It was a very cold night in January. I'm driving on the highway and into the passenger seat comes Dad. I could feel him settle in. He had a very distinctive lean to the left, because of the way his back was.

'Also, you know how you know the sound of people's breathing? How you can tell whether it's your son or your daughter in the room? It was Dad. He rode with me for about ten miles.

'It was incredibly real and completely transforming. I was almost giddy. I was hoping he'd stay.'

Karen never sensed his presence again. Her father, she believed, had been saying a final goodbye.

Yet some loved ones can linger for years. This continues to be the case with her aunt's son, who drowned 35 years ago in a fast-flowing river.

'On a very regular basis, Allan comes and sits on the end of her bed, and they have a conversation,' Karen said. ' "And don't tell me I'm crazy!" my aunt always says.'

Back in 1917, Sigmund Freud labelled all such visions and sensations as 'hallucinatory wishful psychosis' - and his view remains popular in the medical profession. Since then, however, a great deal more has become known about hallucinations.

People held in solitary confinement for a long time, for example, are known to hallucinate. This takes the form of random, often paranoid imagery, and it's accompanied by agitation, panic attacks and general mental disintegration.

But widows and widowers are clearly not in this state when they see or sense their loved ones. Nor are they likely to be alone for days on end in tiny windowless cells.

What about the theory that sheer longing for someone could cause a hallucination? Unfortunately for the sceptics, this falls at the first hurdle. Think of all those long-term lovers who leave people heartbroken when they run off with someone else. No one reports having visions of them.

In any case, the vision may not even be of someone close to you. That was certainly the case when a lawyer - interviewed by psychologist Erlendur Haraldsson in 2006 - had an unexpected encounter.

One day, as dawn was breaking, he was coming home from a dance at which he hadn't drunk any alcohol. While he was walking over a hill, 'a woman came towards me, kind of stooping, with a shawl over her head.

'I didn't pay any attention to her, but as she passed I said "Good morning" or something like that. She didn't say anything.

'Then I noticed she was following me. When I stopped, she also stopped. I started saying my prayers in my mind to calm myself. When I came close to home, she disappeared.'

But had she? The lawyer's brother, who was awake, greeted him with the words: 'What is this old woman doing here? Why is this old woman with you?'

The brothers lived with their father, who worked at the local psychiatric hospital. A few hours later, they were told by him that a patient at the hospital had just died.

When the brothers investigated further, they found out that she exactly fitted their description of the old woman.

Clearly, whatever had caused the woman to materialise after her death had nothing to do with the lawyer suffering from isolation. Nor had he been longing to see her.

Yet, bizarre as it was, his experience would not have amazed our ancestors.

Throughout most of our history, everyone has known that those who die can return as anything, from a sigh to a physical presence. Our ancestors simply assumed the dead continued to watch, console, guide and even meddle in their affairs.

Collective delusion? Mass hallucinations? Or perhaps our ancestors have something important to teach us.

I knew she had been ill. I was living in Santa Monica & she was in Spokane. I was reading in my living room when I sensed her presence. She "told" me she was leaving; she would be around for about 2 weeks and, after that, we wouldn't have contact as she had to go to a different "place" to continue her lessons. The next day I received the call. I attended the funeral and wake.

About 2 weeks later, back in my apartment, I again felt her presence. She "told" my she was proud of me, to stay focussed the way I was and that she was going now and would not be in further contact.

That was the last contact I had.

Thank you for the article. I've learned through direct experience that what is contained in this article is true for me on several levels.

At 16, I spent 6 days in a coma after being 'pronounced DOA'. During that time, I 'sat' in a corner on the ceiling of the hospital room watching as my body was worked on. Some of it's a blur, but much of it remains with me-my parents distress, doctors and nurses scrambling to work on me etc. and the realization then that none of them could see or hear me even though I tried to communicate with them. There are other things as well, the Light, the Presence, the Voice that spoke and told me that I still had 'things to do here' and other messages that came through at the time.

I've almost left the Earth twice more and I want to say that although we may not feel 'ready' when it is our time (my overwhelming feeling the 2nd time was that my very young children needed me and I prayed that). Both of these times, I was in a different 'place' than I am today and I was very afraid. I now know there is absolutely nothing to fear and we do not 'end' with the shedding of this physical body.

In 2011, with a two year old grandson in my care, my father dying of metastatic cancer and my family home from various parts of the U.S. for Thanksgiving I was again admitted to the hospital quite critical. This time, I asked the Universe why now? Why with the family being in such need was I going through this. I asked what soul lesson there was for me in this. Then I gave it up-I gave all my despair and worry to the Universe and immediately I was released from it. There was no fear involved. With total acceptance of whatever was to be, what I immediately heard was "you are strong, you will be fine. The lessons aren't for you alone. Trust."

Many other 'answers' did come that were for me at the time. The greatest one, that we 'separate' ourselves from Source, God, Creation, not the other way around-each time we think the answers are outside ourselves. Creation always supports us, even when it doesn't feel much like it at the time. Of this I am now certain. (my experience, you think what you want.)

I spent 40 days extremely ill, with CO2 levels through the roof and unable to breathe. From the onset to my insistence that I couldn't get well in hospital and that if they didn't release me I would sign out against medical advice, no one (except me) thought I could go home and be well. I was released on Thanksgiving day. The following Monday a pulmonary doc told me I would never get better and I laughed. I told him I'd do what he said for a short period of time, but that we would be discontinuing meds asap and that I would provide a list of the 'alternative' methods I intended to use. The first visit, 4 days later I had to be taken in by wheelchair. The second one week later, I walked. By the 1 month mark, I said now let's discuss discontinuing my meds and 6 months later, he said I don't think I need to see you again-call if you need me. I have not. He has learned that he doesn't have all the answers. That herbs and nutrition are great healers. That he cannot make the judgement for someone else of how their life will be or end. There have been many other lessons.

Ok enough of that part...my father made his transition at home with us January 1, 2012. He had been 'unconcious' for close to a week at the time. I feel blessed that I could be there to 'pray', to hold his hand, to tell him it was ok for him to go, we would all be fine, we would assist my mother, he didn't have to stay any longer if he was ready to go.

My father appeared in a dream the next night. He was very young, dressed in his finest pinstriped suit. I was at work and had a struggle to get away to see him. We sat and had lunch together and he seemed confused saying he couldn't find his way home. I said Daddy, you are home, no worries and I woke up. The peace that washed over me in that instant is indescribable. A few days later, I saw him standing next to a building, smoking a cigarette, in a stance that was common for him in my youth, one knee bent against the wall, with his curly red hair blazing. He nodded to me and smiled, and when I looked again he was gone. He looked so different in these 'visitations', his illness had taken so much from his physicality-I can be nothing but happy now as I remember him. I believe that was his message to me-that he is 'ok' now. A blessing that.

My grandmothers have visited in dreams. My husband has awakened to witness a woman in white watching us as we sleep (he tends to think what I 'do' is whoohooo, but his life experiences are opening him more and more everyday). I asked how he felt as she watched us (he shook me awake, thinking at first that I was standing next to the bed.) Rather than being 'freaked out' he said he felt very peaceful and safe (as did I).

I have very dear, honest, loving friends who help others to the Light, many of which have had the kinds of 'visitations' expressed in the article above...sometimes these things are preceded by a 'scent' as if the room is perfumed with something out of your childhood memories (for me it's great gran's apple pie), sometimes it's the radio or television or something else turning on and off-my great aunt used to save and hide pennies and dimes all over her house like a game. When she passed, her daughter had the walls completely washed and the entire house painted. After that (seemingly impossibly) pennies and dimes started showing up all over the place and a hall overhead light that had not worked in years (and had repair attempted) suddenly started coming on and off. (Our proof of existence on the otherside?! She would definitely want us to know and so that's how I take it.)

So be open. Be Love. Set aside fear and preconceived notions. Trust in something greater than yourself. If the other side knocks, ask in your protection and think about answering the call.

I don't speak of my experiences often, and only touch on very basic things here but we are miraculous be-ings. So just BE who you authentically are. Love, kristyne

I have two stories to tell... neither of them truly spectacular, but they made a believer out of me (actually I was already a believer; they made a "knower" out of me).

First story (second in chronology): My father passed away on Christmas Eve day, 2003, and my mother was in a rehab hospital. So early next year my wife and I had an estate sale in the apartment they had been living in. We sold all we could sell, and what was left we were giving to charities and second-hand shops. People were coming the next day to clear the remains away. I was alone in the apartment straightening up and putting things in boxes, when I remembered that my father had purchased several gold coins some years ago, and they hadn't shown up amongst all their stuff. I was leafing through some files in my father's former study in hopes of finding the coins there, when suddenly I found myself in a bee-line for the bedroom, finally standing in front of the high-boy dresser that belonged to my father. I pulled a certain drawer completely out, looked into the hole, and there at the back were the coins. There were no "words" telling me where to go or what to do, I just knew what to do. However, I did sense my father's presence, so there was know doubt where the direction was coming from.

The second story (first in chronology) is more like a traditional "ghost" story, and as such it's even kind of fun to tell: Years ago, a friend and I were living in an old farmhouse that friends of mine had purchased, and the two of us were there to gut and remodel it. Rather than drive the hour plus to and from town each day, we just lived there. It was a small house. My "bedroom" was the living room, which at the time had only exposed-stud walls. At one end of the living room was a door that led to the attic, half of which was finished as a room. So it was an evening in the fall, and Jim, my friend, had gone down the road to talk to Gus, a retiree from the city who had lived there for some years. I had let my dog out for his night-time self-walk, and I sat down to spend a quiet evening reading some Buddhist literature, as I had recently made that connection. At a certain point my dog started barking fiercely from the driveway, where there was a ground-level door, jammed ajar, that led into the basement (the house having been built on a hill). Then, just as suddenly, he stopped barking, but at that very same moment the atmosphere in the house "lit up", as if the very air had been chared with 10,000 volts of electricity. I sat bolt upright. Then, I heard coming from the attic room just at the top of the short flight of stairs, a very distinct male voice moaning, accompanied by measured hard thumps on the floor. This was not some indistinct sound off in the wind somewhere; it was definite and most audible -- right there. Remember, this was a small house. Although my hair was practically standing on end, I somehow had the presence of mind to address this being directly. I acknowledged his presence and told him that there was no point in his trying to visit his former life (I assumed that he had once lived there), that doing so was an obstacle to his moving on to whatever was next for him, and that he should go. As soon as I'd said that, the moaning stopped and the "light" and the charge left the room as if someone had flipped a switch off. Everything went back to normal. Later, when Jim returned, I told him what had happened. He looked astonished and told me that Gus had spent the evening telling him about the old man who lived and died in that house, and who, in his last years, was in great pain and walked with a cane. He figured they had "pulled him in" with their talk.

Interestingly, as I write this, an old friend and mentor of ours is in hospice, probably just hours from his own passing.

I have never had an experience, even remotely, like these. At least that I remember or am aware of. I think about this sometimes and wonder why I haven't. I think I have never wanted to. Encountering anything non-physical so to speak, I don't think, ever occurred to me in the first place, but when, eventually, it did, it was from hearing about people being possessed and demons. Naturally, I didn't want any part of that, so maybe that scared me away from similar possibilities.

Thanks all for sharing these experiences because to me these are the important things in life. I'm thinking a lot about my mom's impending death and my brothers passing so I love hearing about your connections. I feel so much relief from believing my loved ones are still able to be with me. I'm angry with myself because a friend is dying and I'm scared to go see her in the hospital. Can't get up the courage to go see her and say goodbye. Hope I can pull it together before she's gone.

Dear Brian,

I was struck how you described being angry with yourself for lacking courage, because that's exactly how I would describe my state of being over the past fee weeks, and I don't understand why. There's a growing list of things that I'm procrastinating with because I feel a lack of courage, and I feel stuck, tired, and angry with myself for it.

What does it mean? Is this a message that we need to be kinder to ourselves and forgive ourselves for our meekness? Is it a sign that when it comes to matters of spirit, that we need to stop relying on willpower and personal effort in accomplishing our life purpose - that maybe there is a path that involves humility, faith, and complete surrender? I'm just rambling here, I don't actually know any answers.

What is it that we're so afraid of? I felt something similar near my dad's passing, when I visited him, and I could barely say anything as he was drifting in and out of medicated consciousness. Objectively I can see that I would have risked nothing and gained so much by laying my heart bare to talk to him and sing to him in his final hours, and it is so easy to scold that portion of me that felt immobilized by fear.

But intuitively I can see that scolding is not what is needed. Somehow there is a little child there who is afraid of what might happen if she shows herself, and she needs embracing, not scolding.

Somehow I feel that I need to forgive and accept that this is what's going on with me right now, and it won't help anyone to try to suppress and push past these feelings.

A suggestion that I've read, Brian, is to find something related that you are willing to do without pushing yourself. Maybe call or visit with the family members, or go visit your friend for just a few minutes without the pressure of needing to say anything.

With my dad, I didn't end up saying anything profound, or even saying goodbye, really; I did help get him to palliative care though, and I did sit quietly beside him for a few hours while he slept, and I did provide support for my mother. I had wished I had been able to say more to help ease his passing and comfort him, but after his passing I feel comforted by his spirit that it was enough.

Peace and light,

Trish

In your posts, Brian and Trish, I read that it's difficult to watch as those we care about make their transition if we do it from a place of fear and our own wanting. Wanting more time together, fearing what our own lives will be without them, even regretting when our relationships with them have maybe not been exactly the way we think they should have/might have been. Often we're also faced with bearing witness to their suffering or pain and we know we don't want that for them and we also may suddenly really feel our own 'mortality'. (I'm speaking from my own experience here again, so take what resonates with YOU from this post as always.)

To Brian, you've hit it the nail on the head when you speak of 'connection' and so whether you go physically and spend time with your friend, or whether you go into the silence of your heart and higher self and 'speak' to her, you will have been 'heard'. I truly believe because of our connection our loved ones know we are 'sending' those thoughts of comfort, love, acceptance or non acceptance of their going. I believe it is in part those things that allow some folks to 'leave' in the presence of their families, while others seem to 'wait' to hang on until all the family has left and then feel 'free' enough to pass from the physical world.

During a period from 2000 to 2002, eight of the elders in my family passed with various cancers. In 2 years, our family dynamic drastically changed. Most were cared for at home, some with hospice, but all surrounded by what family could be there and bare to be. Not everyone could. I can say, it is a great gift to the living, when you are able to support a family member in their passing. To keep someone at home, though the work can be tremendous and the pain felt during the process seem overwhelming, to know you have done everything you could is a gift to both them and ourselves. It may at times also be necessary to be forgiving of those who are/were unable to do the same. I have also seen many families break apart after losing someone because someone did 'more' or less than someone else. The departing Soul would NOT want that. Another opportunity for forgiveness arises there.

When my dad was very ill in 2010 and doctors had said he had 3 months to live I was angry. No one, not even the best doctors know when our time here will end. For some people, just the pronouncement, can make it true because it alters their own 'belief'. My father lived that to a 'T'.

He was a strong wonderful man but he had watched all his best friends as cancer took them. For him, the pronouncement was enough. In his 'end days' we spoke, just he and I, of whether he was 'ready', how his life had been good, that his only concerns were for my mother, and that he had made his own peace with this devastating illness. For me, it becomes a testament to live as if there is no tomorrow and love as much as we can right now.

I promised I would pray with him when he could not, that I would be there for my mother, and I told him it was ok. I told him I didn't believe the doctors had the right to tell him he only had 3 months, but if he felt he had finished what he came here to do we would all be alright. That it was alright to go home. I also spoke to him about what messages and beliefs had changed for me since my own nde's-something we had never discussed before. I feel blessed that we got to have that.

Not all of us can physically or emotionally handle being in the presence of illness, suffering or great pain. It is not something to be ashamed of, true we need to push past some things, but we also need to be cognizant of whether our discomfort is about 'them' or more about our own. If you look at that a bit, you'll find ways to 'communicate' and ways to support those around them that are also in pain.

I don't know from your posts how many losses you have faced or how while growing up 'death' was discussed or grief approached by your family. I am amazed as I attend or officiate 'celebration of life' services how different each family is in their belief, acceptance, emotional state, etc. I've told my family to celebrate when I'm gone because I will be dancing and I will feel them. I encourage my daughters (and you as well) to have no regrets and to tell those you love that you do, often. Love doesn't always need to be 'spoken', we show it in myriads of ways. You may have witnessed it already, in the tender ways grandparents or the very elderly who have spent their lives together often don't need to speak a thing-just holding each others hand is enough.

To Trish, your story is beautiful, your dad didn't need your words, what was in your heart was in his heart because of your connection. That never leaves us. I wouldn't be surprised if your dad comes through in dreams or other ways that you will recognize (if you want to). He knew you were there.

I believe prayer is something entirely different than many of us have thought or been brought up to believe. I think our 'prayer' is the thought. 'Pray without ceasing' (to me) means every thought - every single one, is a 'prayer' effecting what we are 'creating'. When we sit with another, in loving them, through pure pleasure or pure pain and everything in between, our thoughts for them are also a prayer for ourselves. One is not different than the other.

Connection. When our stories touch each other it is also connection. I truly believe we are individual sparks of One great fire. We build it, we tend it, we share it, even when it seems to be only ashes, our sacred breath gives it life again.

I apologize, I didn't realize I had written a book. So I will end with this-a favorite poem I read to my children from Shel Silverstein-

All the Woulda-Coulda-Shoulda's layin' in the sun. Talkin' bout the things they woulda-coulda-shoulda done... But those Woulda-Coulda-Shouldas all ran and hid from one little did. Love you. kristyne

Trish and Brian,

Several years ago I turned away from a friend who was dying, out of fear, and I've always regretted it. But then I look at who I was then and try to forgive that lack of response. I do forgive that, but there is a lingering feelilng of sadness that may never go away.

When my dad passed, he did so quickly, so I didn't have a chance to really be with him. But I do regret not having had the courage to tell him beforehand that I loved him. I think he knew, but in the long past he scorned me for showing emotion, so something in me vowed never to expose myself to that with him again -- even after seeing that in his old age he became very emotional himself. In other words, I didn't change with the changes. Well... we do what we do and don't do what we don't. Can't change that, so it becomes part of that sadness. That's okay.

In my mother's case, I was with her the night she died (but was asleep at the moment when she died), and I tried to support her, but again because of my gun-shyness around expressing emotion, I didn't do that nearly as well as I might have. More sadness.

Right now a very good friend (and former spiritual teacher) of my wife's and mine lay in hospice. I felt the same fear come up around visiting, but we both went and sat with him, with a few words but mostly just with our loving presence -- for just five minutes (limited to that for his sake, he being tired and depleted). But that was enough. Something was communicated and completed.

Brian, my advice is that if you can bring yourself to visit your friend, just go ahead without thinking more about it. You don't have to say anything profound or deliver any formulated words for the occasion. Just be there for her; forget about Brian altogether. She may even have something for you... you never know. If you truly can't, then recognize that and be at peace with it.

Trish, I agree that you were there for your dad and gave him your loving presence, which he surely felt. I think you can trust your feeling about something being completed. You did what you could; I completely understand your experience (as you can see from what I wrote just above.)

About fear of moving forward generally: There's a saying in German that translates as, "Nothing is ever eaten as hot as it's cooked." That means that our thinking about coming events or actions tends to be far worse than the reality when it arrives. We're so conditioned to thought proliferation about just about everything. Sometimes I wake up in the morning with a feeling of absolute dread (it's something very old and deeply ingrained). I know that this is just a "thing" that arises in me, and I know that it's inviting me to let my thoughts and emotions build on it. In the past, this is what I would do -- much to my distress and disempowerment. But now I just lie there with it, not pushing it away, but just looking and feeling. I label it "thinking" and "feeling". This stops the mental proliferation and the grip of emotions, because with that "action" I've become a mere observer of the phenomenon, not a part of it. The result is that the dread subsides, and as soon as I get up, my way is clear.

And it's the same with fear about doing anything. First comes discernment about whether or not the action/decision is good and worth doing (let's say it is). Then comes the feeling of fear of doing it. Next the labeling ("fear") and the observation of that emotion. Finally the "doing" anyhow -- the step into the unknown -- with the faith that this is the right thing to do and that things will work out in some way or other. Truly, we need to develop tolerance for the fact that nothing in life is truly guaranteed or foreseeable. And yet we can have faith. Why? Because we know (deep within) that we are bigger than even this life, so even if we lose we haven't really lost anything. One Buddhist teacher told his disciples, "Invest in loss" -- that is, when it comes. Truth is we really don't know what will come. But we can act anyway. What a beautiful human gesture that is in the face of the Unknown...

These are things that I am still working with and will continue to work with because I'm still in school here (and not at the top of the class, for sure), and life can end at any time, along with the opportunities that it offers.

Dear Kristyne,

I totally agree with you about being able to send other beings (humans and animals) your thoughts and feelings without necessarily needing to speak them out loud, and I believe you can still do so even after someone has passed on. I also resonate with what you said about loved ones being able to sense whether or not you're ready to let them go yet; perhaps that's why my dad chose to leave while I was at work and while mom was just walking to the hospital from the parking lot; perhaps he knew we weren't ready to be there with him. I was still holding onto some kind of denial or hope that if he just got a break, he could still recover; mom was just exhausted from trying to take care of him by herself from home for so many weeks.

I can understand your anger at the doctor's pronouncements, and how suggestions like that can be self-fulfilling. I felt similar about my dad's condition - from my perspective, things only seemed to deteriorate beyond repair after he was pumped full of chemicals, and then much of his suffering was from the side effects they caused; it was hard to see my parents be so trusting of the medical system. I understand though on all sides that everyone is doing the best that they know how; I don't hold any hard feelings about it anymore.

We held a 'celebration of life' for my Dad, about a month after he passed away, so we had had some time to process our grief a bit. People gathered from all over and we sang songs, laughed a lot, shared stories, and connected with old friends and family with food. People came out of there saying it was the most fun they had had in a while.

Funny that you mention dreams, Krystine - for over a year after he passed away, Dad was showing up in my dreams like crazy! I even had to tell him to give it a rest after a while; I talked about it a lot in this post: http://www.gatheringspot.net/topic/dreamsdreaming/dreams-departed

Yes! I love what you said about praying. Apparently the Sufi mystics say, "God makes us, using our prayers." From the book I'm reading, "And the quality of prayers that you offer becomes the radiance of who you are."

I've never been much of a praying type; back when I was trying to formulate a mental picture of God or Jesus whom I could try to talk to, I would get frustrated trying to 'listen' for a response, all the while trying to establish a connection by imagining it into place - an exercise in futility! It resonates so much clearer and naturally that 'praying ceaselessly' is being in present connection with each moment and responding with compassion and humility according to our unique divine purpose.

Love, Trish

I did read and follow the posts about your dreams, just seemed everyone had a great handle on it all, including you Trish so I didn't post at the time. I had recently lost my own dad, and was struggling with how to really explain the loss to my grandson because even as little as he was my dad was really important to him (he also lost his other great grandpa shortly after and then his best buddy-his dog.) He has learned loss almost before anything else in this lifetime.

(His mother, my youngest daughter, left his dad shortly after that and left him with dad as well.) Another reason I don't always get here or reply right away. I am too busy 'grandmothering'. It is both the most important and most rewarding 'job' I've ever had. I take the responsibilty very seriously.

He was seeing what he called 'monsters' at the time dad passed. Instead of telling him there were no such thing (like the rest of the family) I asked him to tell me what they looked like. He described lights and colours and I got the sense that they weren't monsters at all. We began talking about where we might have come from and where we go. About God and heaven and angels in ways a small child might understand.

We talked about how Oscar the grouch just tells everyone to SCRAM and so he began doing that when he was afraid. His monsters disappeared. Now he reminds us not to be afraid. If someone forgets to say a prayer before we eat he stops us and says what he feels needs said. There is nothing formal about his prayer. He has learned to ask for help when he needs help and to know the help is there. He's also drawn to my crystals and rocks and knows the names of many. If he gets hurt he places his hands on the hurt and I place mine over his and we 'see' it healed.

He looked at me one day and said "Ya Ya, mama don't believe that. Mama don't believe God and his Angels are there to help us like you do. " I said mama doesn't have to, God's still out there doing the work. He said "Then let's just ask God to help mama too." And so we do.

I know there are those that have different views on faith, religion, etc. but it remains my belief that God/Source/Creation works through and with us even when we don't believe it at all. It's true for me in all the directions my life has taken-some of them utterly surprising and all necessary parts of my own Soul's unfolding.

I ask as I fall asleep for the dreams and lessons to come. To be in the presence of Ascended Masters, Guides and Angels and to allow the lessons to come in whatever ways I am ready. Love to you all. kristyne

Gentle lessons-please God. Gentle ones. I'm moved by these stories. I hope I can have the strength to go see her. Trish-I have been so frustrated by a lack of response by what I imagine God to be when praying. Maybe it's faith I lack. I want proof! Show me you're here God! I pray small spontaneous prayers for family and ex's but more often for strangers. Sometimes for a person who looks sad or lonely. Sometimes for a public figure. I prayed for Bush and Cheney a couple of times and wished them well. It was a good change from the 8 long years of hatred and loathing I felt. I don't seem to be that person who has faith in his prayers doing any good but I want them to so badly. I Hope that is enough.

I hope you will not beat yourself up too much around your father's passing Trish. You were quietly there and from what I have seen about how the dying orchestrate things to a tee, that was the perfect thing for your dad. Also, he may have really needed you to be away so he could go. It might have been too hard for him to leave otherwise. I'm so sorry for everyones losses. My heart goes out to each one of you.

Dear Bob and Brian,

I do trust that sitting with my dad was enough, and I think you're right that he needed us to be away when he passed. I've received plenty of confirmation from him since, and after I posted my last message in this thread I had another dream with him in it that night.

I was sitting at a small table with someone next to a galley kitchen, where Dad was making some breakfast, quiet as usual. It took me a few moments, but then I became hyper aware as I looked around the room. "Am I dreaming?" I asked. No one answered, and my dad kept cooking. "Tell me, am I dreaming?" I asked again to the person sitting across from me. "Well... yes you are," she said. I looked around, wide-eyed. "It feels so real though," I said. That was pretty much what I remember, pretty ordinary but nice. On Father's Day, my mom posted his picture on Facebook, and I didn't feel any sadness because I really do feel like he's still here.

Thanks for your reminders about detachment and faith, Bob. For me the 'stuckness' is in actually taking those steps of action, and not falling into contraction and automatic behaviour or procrastinating. What I've been reminding myself is that I *have* been making small courageous steps in my personal, family, and online life, and they have trickled through to other areas without me even noticing it. That I am holding an intention to express myself genuinely and to connect with the deepest core of people is like planting a seed and giving it nourishment; I need to be patient and keep observing and detaching from the fearful thoughts and emotions. Already I've seen a huge change - that I no longer hold myself in shame or self-punishment when I come out of a situation realizing that I had fallen asleep halfway and went on auto-pilot.

I wrote down a quote and a personal intention that I've been keeping with me all week:

"Being courageous means choosing to love in the face of fear, choosing truth in the face of invalidation. Fear is just a messenger."

"Take small courageous steps. Act on small spontaneous urges. Give thanks for the many small miracles. Be prepared for pleasant surprises."

Energetically, I feel as though I am moving through a block in this area; similar to the feeling of dread that you describe, Bob. It's like a heaviness or 'stuckness' at my chest. Intuitively, I would say that there seems to be a lot of expression just waiting to burst through the barrier, but my thinking mind doesn't know what it is (or perhaps is afraid to find out?). A thought came to me, perhaps the best way to clear the barrier is to start letting that expression come through as though the block is not there. Perhaps I might start a thread where I do some video sharings - I've thought about doing something like that for a while.

Peace, Trish

I like and agree with what you said, Kristyne:

"I know there are those that have different views on faith, religion, etc. but it remains my belief that God/Source/Creation works through and with us even when we don't believe it at all."

What I had come to realize, same as you, Brian, is that I was trying to fabricate a relationship with God through my mind and imagination, and trying to control the experience in my own way. I also limited my 'listening' to God to this imaginary channel that I created, and got angry when I didn't experience the results I was hoping for.

At some point, I came to the realization that what I was doing was not really prayer, this desperate controlling hope I clung to wasn't really faith, and what I was trying to connect with wasn't really God. For me, what felt right was to leave Christianity and let go of these concepts and habits I had been clinging on to. Deep down though, I trusted what you described, Kristyne - whether or not I was adhering to a certain set of beliefs and practices, I would be taken care of.

What rings true for me now is that God is to each of us as the ocean is to a wave. Imagine the frustration the wave might feel if it believes that the ocean is some separate, foreign entity that it must work to maintain a relationship with! In truth, its entire being is one with the ocean, and the two are never separate. Their relationship can be forgotten, but never lost.

I like the philosophy that all of life is a communion with God (lately I've been using words like 'source' and 'universe' because I still tend to carry some anthropomorphic associations with the word 'God'). Every moment there is some opportunity for understanding and growth, to learn and practice, and with the amazing freedom to choose.

It's possible that we are all "praying without ceasing," whether we are aware of it or not. This may be what the law of attraction is; life answering our conscious and unconscious prayers. May we move into ever more conscious ways of being and co-creating with life!

I think it's beautiful to offer small prayers throughout the day, especially to those with whom we've previously struggled with hatred. When I do pray, I let the prayer settle in my heart and flow through me. An idea that I have is that by creating inner space for the prayer to blossom, we are planting and nurturing seeds of faith. When it is time for an answer to appear or for a miracle to occur, our soul has already welcomed and prepared for it.

It's past my bedtime here. Kristyne, I am intrigued by the idea of spirit guides and angels, but I don't know how I would go about identifying and communicating with mine. I'm a bit nervous that I could end up conceptualizing them and fall into old habits.

Good night!

Peace and love, Trish

I end my day by reviewing for a moment what went well from a soul growth sort of perspective and what I might have done better at. I ask forgiveness of myself and others in any area that it may be necessary whether I realize it or not. I ask to continue my lessons, while my body is at rest and to allow contact with all that is of the purest Divine essence that I am ready to receive and I say thank you for all the blessings in my life. What comes is what I need at the time.

Whatever you're doing is right for you right now because there is no right or wrong - just lessons.

I believe we come in with specific lessons for this time around unless we've come in as Masters to be examples and helpers to others and bear witness to the power of our human/Divine potential. To me Self-Mastery is the reason we are here (again).

Our actions (or reactions) have karmic consequences. My thought on that is to do the best that I am able in this moment and to help others when I can and if I feel I fall short, to do my best to forgive myself as well as them. I truly believe what we do to others we do to ourselves so why would I not strive to just love it all and all I encounter (all my 'teachers')!

Trish, you might like one of my favorite books. By Terry Livingood (his real name) called 'The Bible for Translation from Physical to Spirit', his first work, he also offers "Awakening to Self-Mastery"- having both books, I would recommend the 'Bible' first. I have used it several times with groups and in the midst of times of personal growth and change. It's not your typical study Bible, not at all.

His website is http://www.spiritualmastery.net/index.html and you can get a feel for it there.

of course, again this is all imo. Peace upon your path Trish. with love, kristyne

a Shamanic perspective on transition from Jade Wah'oo Grigori can be found at his site at this link and might be helpful to many of us as well. A well respected and well known healer. I have not copied here as he asks specifically to not do so. Also a good article/opportunity to join his Solstice Ceremony is there as well.

http://www.shamanic.net/index.php/articles/1-assistspiritstransition

In these descriptions of your daily experiences, I find comfort that you guys are struggling with small, but meaty evils too. In my mind, my choice of whether to face fear with decisive intent for a better outcome is where the rubber meets the road. To choose to win!

I woke this morning to raw fear that I might fail with a badly troubled project at work. Then, before I could eat breakfast, I found the client had emailed my manager with unpleasant threats and voicing no confidence in me. Deadline-today! If I failed to overcome the hurdles, it could potentially lead to getting fired or becoming restricted. At a minimum, a substantial loss of trust and money for the company. SO......I had all this raw fear.

I instinctively knew I needed to pray for success because really-it's out of my hands and I'd better

a) specifically ask for complete success, no matter how improbable it seemed and then

b) immediately let go of holding on to that outcome. Someone else is pulling the strings. I began to feel calm.

Wham! smash! I won! It all came together-the hurdles melted away-things began to work effortlessly. What a relief. I said thankyou to that or who made this happen and allowed myself a little selfish credit for the win too because that's in my nature-as long as I didn't take myself too seriously. Wahoo!

Wahoo Brian, glad things went well for you. On the other side, when things have not (imo again), usually there was a good reason and something better comes about even if it takes awhile.

As an example, my hubby has 40 yrs with a major company, he's a great guy, a hard worker with that old fashioned work ethic we don't always see anymore. Every time someone isn't doing their job, it seems he gets dragged into it somehow ie. he's been moved several times to 'take up the slack' instead of the jokers not doing their job being dealt with. So for about the third time in a couple of years he came home p.o.'d because they were doing it again, sending him to a totally different dept.

I immediately intuitively knew it was going to be better for him. (like many husbands and wives we don't always see things the same surprise surprise!) He kicked and groaned but I said give it a chance. What are you worried about? Trust yourself, you're a good guy, it isn't about you getting screwed. Be open minded. Look at both sides. What's good about the dept./what's bad. He said it's cleaner, it's quieter but I've never worked it in 40 yrs, gonna have to learn new stuff etc. I said just go with it. He didn't sleep a couple nights, worried and fretted but by the end of the first week he said it's the best job he's had in the place yet.

So it wasn't about me being right, that isn't the point of my note. It was about just what you've described-stepping back for a minute, trusting enough to let go of the fear, asking in help from a higher place. I only started out writing this to say...when I'm asking, I always say help me with this (higher self, God, Creation, Masters Angels and guides-your choice) release my from fear, I'm accepting of the outcome so bring me ___ or better and better-whatever is in my Highest good. Then I accept what is received with thanks knowing if it appears to be 'less' than expected the Universe is orchestrating what I really need. There's usually been a very good reason and something better has materialized even if it's taken awhile.

Acceptance and gratitude even in the times that seem hard have never been wrong for me yet. Wishing you better and better, more and more. love kristyne

Perfect, Brian. Pray, do your best, let it go, don't take self too seriously. Enuf' said.

That's awesome that you surrendered like that Brian, good job! I don't like that kind of work stress to say the least! I'm really intrigued by the idea of asking for and imagining complete success, however improbable it seems; I'm just not accustomed to thinking like that yet - I tend to sway from mildly pessimistic to mildly optimistic.

I've noticed lately that when I dwell on the frustrating aspects of my work, that more roadblocks seem to come up and add to the frustration. It's kind of addicting though - it takes deliberate effort to separate from that mindset and choose optimism and proactivity instead, and to be honest, some days I just indulge in a little grumpiness! Doing that though is like pigging out on a whole bunch of fast food - not beneficial in the end, for me or anyone around me. ;-P